In the House of Advanced Primates

h.saussy

In French you can say, without blushing, “les sciences de l’homme”; in German you can say “Geisteswissenschaften”; but if you say “the human sciences” or “the sciences of the spirit” in American English, you have the feeling of perpetrating a mistranslation, a misconception, or even a fraud. Why is that? Well, one reason jumps off the page of Jamie Cohen-Cole’s The Open Mind: Cold War Politics and the Sciences of Human Nature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014):

As it was originally organized, the National Science Foundation did not include a specific mandate to support the social sciences. This was because the public, Congress and many natural scientists either equated the social sciences with socialism or did not find them to be sciences at all. … Speaking for the “average American,” Congressman Clarence Brown (R-Oh.) [said]: “If the impression becomes prevalent in Congress that this legislation [for the National Science Foundation] is to establish some sort of organization in which there would be a lot of short-haired women and long-haired men messing into everybody’s personal affairs and lives, inquiring whether they love their wives or do not love them and so forth, you are not going to get this legislation.” (p. 96)

So that’s why anthropologists and others of that tribe have mostly depended on private foundation money in this country. And at the beginning, at least, the bargain didn’t seem Faustian at all. Private money was interested in generating innovative, consequential research, with a lingering aftertaste of the great interdisciplinary efforts that had won the last war for democracy. When there was bounty, the ideas bubbled quickly to the surface. Already in 1955, the Wenner-Gren Foundation was underwriting the founding conference of environmental studies, “Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth.” Also a taboo topic today.

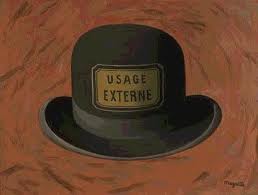

Though Cohen-Cole’s book is a bit repetitive and overuses the passive voice, it tells an important story from which I pull this corollary: The humanities and social sciences aren’t “irrelevant.” It’s the definition of “relevance” that shrank, as the community of interest and support behind academia changed its objectives from building worldwide support for “the American way of life” (pluralistic, democratic, plentiful, permissive) to guaranteeing the highest return on investment. “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small” (Sunset Boulevard).