(Introducing Paul Farmer, Human Rights Program Kirschner Memorial Lecture, June 5, 2014)

Good evening and welcome to tonight’s Kirschner Memorial Lecture. I’m delighted to see so many of you here tonight, a direct acknowledgment of the significance of our Human Rights Program and a hint that our benefactors’ generosity has not been totally misplaced. The questions examined in the Human Rights Program are among the most serious questions raised in a university, and I would say that for us, specifically, in this country, with our history and assumptions, the area of health and human rights has the greatest power to change the way we see ourselves and others.

For many of us in Paul’s and my generation in the United States, the first time we heard about human rights as a field of activism, it was in connection with the denial of people’s rights to free speech and assembly, their right to emigrate, their right to seek redress, their implicit right to representative government. And we learned about this in the context of the Cold War, when it seemed self-evident that people in some part of the world benefited from the recognition of those rights, while people lacked them in many other parts of the world—not only the Soviet bloc and China, but also Latin America, Asia and Africa, where the client states of the great powers all seemed to repress their dissidents with the greatest indifference. Of course, it didn’t stop there. The response to human rights activism by official representatives of the socialist countries and by some of our own home-grown leftists was to point out how inequitably the market system distributed such basic goods as food, housing, education and medical care, goods which, it was implied, were a fair trade for civil and legal rights. The funny thing about this answer is that it was taken just as a rebuke of the West’s hypocrisy. Despite some laudable exceptions, we did not experience, even in the Carter era which made such a noise about making human rights the driving force of our foreign policy, a large-scale effort to wrap social and economic rights around the uncontestable but rather abstract goods of free speech and fair elections at home. The struggle for civil rights and equality within the US, which had concluded in the courts with a handful of imperfect measures for instituting fairness in civil life, did not carry over into an effective War on Poverty. The Great Society spent most of its surplus on weaponry, with a small percentage allocated to nagging our rivals about their bad human-rights record.

The standoff or zero-sum situation—either legal rights or social entitlements—was left exactly as it was because that was convenient for everybody. Everybody, that is, who was concerned with high-level interstate politics. Those who were not so favored, namely hungry, poor, sick or otherwise suffering people, probably had extremely cynical things to say about human-rights discourse, but few people with entrée to great universities and access to world leaders thought about asking them. The great human-rights standoff was a collusion between antagonistic blocs that told people that there were limits to what they could want or expect.

Except that such standoffs can be broken, when the will to see past them is there. Enter one hard-headed, warm-hearted, methodologically-minded, anthropologically trained M.D. with a specialty in infectious disease!

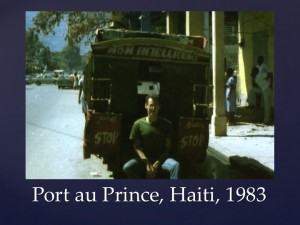

Paul, as you may know, is modest, except when he’s letting his picture be taken on a jitney van named “My Intelligence,” and serious

Paul, as you may know, is modest, except when he’s letting his picture be taken on a jitney van named “My Intelligence,” and serious

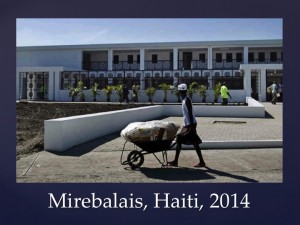

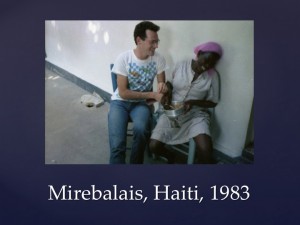

except when joking around with the respectable matrons of his village in Haiti. He began working in Haiti, and dragged friends of his to get acquainted with that astonishing nation, back in the early 1980s, just as Haitians were beginning to see people die of a strange new disease, what would soon be named AIDS. It hit the countryside hard, which might seem inexplicable until you understand, as only someone with Paul’s ethnographic sensibility could, that in Haiti the disease was spreading along channels of contact between people of unequal station and unequal life chances. Tourists from abroad pairing up with local men; employers pairing up with their servants; blood plasma donors pairing up with dirty needles; soldiers and truckdrivers pairing up with women in the villages they passed through. The epidemic furnished an X-ray of Haitian society, showing who was protected and who was most vulnerable. When effective therapies became available, turning HIV from a death sentence into a manageable chronic disease, Paul and his co-conspirators at Partners In Health, Ophelia Dahl and Jim Kim, decided they were going to reverse some of the inequality they saw around them and offer free testing and treatment in their mountain clinic. That act of folly begat others, and I am sure that in the world of development assistance and international public health, many imprecations were pronounced blaming Partners In Health for upsetting the established priorities and triage rules. They had taken a specialist issue and made it into a matter of universal concern through the category of human dignity They were doing what public intellectuals do—taking expertise public. From then on, conditions that had been thought to be hopeless in poor countries were amenable to treatment, and every patient cured was a living rebuke to the former habit of writing them off. Needless to say, the patients had only one complaint, that Partners In Health weren’t doing more, and faster, and over a greater area. With their donors and partners across the world, they are making the effort, again and again.

except when joking around with the respectable matrons of his village in Haiti. He began working in Haiti, and dragged friends of his to get acquainted with that astonishing nation, back in the early 1980s, just as Haitians were beginning to see people die of a strange new disease, what would soon be named AIDS. It hit the countryside hard, which might seem inexplicable until you understand, as only someone with Paul’s ethnographic sensibility could, that in Haiti the disease was spreading along channels of contact between people of unequal station and unequal life chances. Tourists from abroad pairing up with local men; employers pairing up with their servants; blood plasma donors pairing up with dirty needles; soldiers and truckdrivers pairing up with women in the villages they passed through. The epidemic furnished an X-ray of Haitian society, showing who was protected and who was most vulnerable. When effective therapies became available, turning HIV from a death sentence into a manageable chronic disease, Paul and his co-conspirators at Partners In Health, Ophelia Dahl and Jim Kim, decided they were going to reverse some of the inequality they saw around them and offer free testing and treatment in their mountain clinic. That act of folly begat others, and I am sure that in the world of development assistance and international public health, many imprecations were pronounced blaming Partners In Health for upsetting the established priorities and triage rules. They had taken a specialist issue and made it into a matter of universal concern through the category of human dignity They were doing what public intellectuals do—taking expertise public. From then on, conditions that had been thought to be hopeless in poor countries were amenable to treatment, and every patient cured was a living rebuke to the former habit of writing them off. Needless to say, the patients had only one complaint, that Partners In Health weren’t doing more, and faster, and over a greater area. With their donors and partners across the world, they are making the effort, again and again.

This is what happens when you feed the public intellectual that lurks within many a mild-mannered clinician or social scientist or even humanist.

Sir Amartya Sen has observed that when people lack the means of survival, they are unable to pursue such long-range goals as fashioning an equitable political order or balancing freedom of speech against the social good. When, on the other hand, hunger and disease are kept at bay, they can do more for themselves. And living, as we do, in an era of great wealth and astonishing scientific discovery, this ladder connecting social and economic rights with civil and legal rights can, should, must be maneuvered into place. The responsibility is all of ours, at least theoretically, but someone with the will to show what can be done is needed to drive the lesson home. One such person is here before you tonight: Paul Farmer. Although I’ve known him since we were both 18, I have told you only a few things about him and he will doubtless reveal more secrets in his talk, which is entitled “Health and Human Rights: Lessons from Haiti and Rwanda.”