I’ll be using this title to compile some reflections on the NSA spying scandals. Much of what I say will be obvious. If you want to have friends, don’t treat them like enemies. Don’t spy on them and don’t lie to them about what you did if there is the remotest chance of being found out.

I can imagine that there would be a justification for listening in on suspects already identified as “of interest” in a developing case– this is just acting on what is known as “probable cause,” and although not entirely charming, passes the prudence test (does the behavior result in tangibly reduced risk for the people you are responsible for and care about? If yes, check the box and go ahead, though with misgivings). But it’s in the nature of an uncontrolled, secret program to expand as far as the money will take it (and there’s always more money), until the spying apparatus is pretty soon listening in on everybody who is connected to everybody who might be of interest in a potential case that might eventually surface– which means everybody. It’s quite a thing, mathematically speaking, to stay on top of the trillions of relationships that obtain among a billion or so people. But I’m not proud that we’re accomplishing this triumph; it would have been a better cause for pride if we left more people alone.

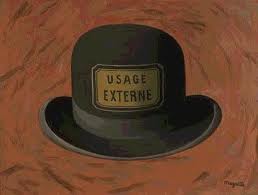

Expanding the definition of “national security” to the point that it includes eavesdropping on all parties to any negotiation in which we and our allies are involved is simply a sign of pathology. People who are deeply mentally sick alienate their friends pretty quickly. Put otherwise, it is hard to be a friend of a person who is paranoid and prone to violent outbursts and claims to be the world savior– and who taps your phone and email. Such a person, if you have the poor luck to be stuck on an island with him or her, I would style the Lord of the Files.

And that is the person that the US has become. Blame is raining down on Obama, and the question (for those who care) is, as it was for Nixon and Reagan, “what did he know and when did he know it?” According to the White House press secretary, he didn’t know anything. But we knew that was going to be the answer. The fact that repugnant opposition politicians, who would do ten times worse if they had the chance, are jumping in to score points shouldn’t dissuade us from asking the question. But I don’t think it matters so much what Barack H. Obama, Esq., knew. The presidency is a legal person, like a king under the old “two-bodies” theory, and in the transcendent sense of that personality the presidency knows, authorizes, and is responsible for a hell of a lot, and it has been so since the XYZ affair was rattling the ruffled cuffs of the young Republic.

What was Obama’s reaction when he learned about these nifty intercepts that gave him a preview of what our friends were thinking (but not, apparently, what the Russians or the Chinese were thinking)? What kind of courage would it have taken for him to push it all aside and say to the Director of National Intelligence, “Cut those wires and fire those spooks. I don’t need to tap the phones of our most trusted allies. We can compete in the big old world on a fair-and-square basis”? Did he think, “Well, this is not totally kosher, but I didn’t actually order the surveillance, and it might come in handy some day after all.” Did he have an impulse to reject the Faustian package, only to receive this remonstrance from the spook in charge: “Sir, this intelligence could be of national importance. It could save lives. It could make the difference between Boeing winning a contract and Airbus winning it. Your personal moral quibbles must cede to the national interest”? I don’t know. I suspect presidents don’t like to be called choirboys.

But a salient piece of Washington folklore was uttered by a member of the policy circle most likely to have the task of making up justifications for the US President being the Lord of the Files. Mike Rogers, a Republican member of Congress and head of the House Intelligence committee, offered, according to the Guardian, the following interpretation of twentieth-century history:

Going further, Rogers claimed that the emergence of fascism in Europe in the early 20th century could be partly explained by a conscious decision by the US not to monitor its allies.

“We said: ‘We’re not going to do any kinds of those things, that would not be appropriate,” he said. “Look what happened in the 30s: the rise of fascism, the rise of communism, the rise of imperialism. We didn’t see any of it. And it resulted in the deaths of tens of millions of people.”

I don’t thing Congressman Rogers would pass a high school history test. What dates are associated with (a) the rise of fascism? (b) the rise of communism? (c) the rise of imperialism? Half-credit for (a), Mr. Rogers (the conspicuous events of the 1930s do include Hitler’s election in 1933, but fascism got its start in Italy in 1922); zero credit for your other two answers.

However, what he is parroting is a familiar line based on at least a fragment of fact. In the first decades of the twentieth century the US had a Black Chamber, or cryptanalysis bureau, based, as much of our present spying activity is, in a commercial telecommunications node (in that instance, the Chamber was hidden in a firm that compiled telegraphic codebooks). After 1919, Henry Stimson, Secretary of State, is said to have declared, “Gentlemen do not read each other’s mail,” and disbanded the Black Chamber. It was pulled back together in a hurry in response to the next war (I am getting this from David Kahn’s 1967 book The Codebreakers, a favorite of my father’s).

Now perhaps Stimson’s code of ethics did not prepare the US for conditions as ungentlemanly as those endured by the combatants of WWII. But Mike Rogers, twisting the anecdote, is demonstrating a degree of paranoia and self-centeredness that is quite magnificent, even for the spoiled children of our elected assemblies. He is saying that the fact that we were (allegedly) not spying on the Germans, the Russians, the British, and the rest accounts for “the rise of fascism, the rise of communism, the rise of imperialism… the deaths of tens of millions of people.” Astonishing! Where is a global policeman when you need one? Why, indeed, did the US not steam forth in 1931 and whack the Japanese who were overrunning China, invade Germany in 1933 and slap them around for their poor judgment in electing Hitler, parachute into Windsor Castle in 1757 and make old George say uncle and give Bengal back to its Nawab? Why can’t we poke our NSA earbuds into every wire and satellite and issue executive orders about every damn thing we please, lest somebody, somewhere, get up to some evil? Foreigners are all right, I guess, if carefully observed and called to order at the slightest sign of going wrong.

For all I know this has been said before, but: the anthropocene is a world-concept.

For all I know this has been said before, but: the anthropocene is a world-concept.