So now the PEN society (of which I’ve been a member for many years) has issued a Manifesto on Translation. Well, why not? Translation matters; it’s literary activity; it requires expenditure of energy and brainpower; it changes minds and modifies worlds. So it deserves attention.

But a manifesto? I confess that I don’t much like the manifesto genre. I used to parody it back in college, mainly to sneer at its pretentiousness. For manifestos hector and tell you what to do; they speak for a collectivity; they condemn rivals; the right side of history is their happy place. With none of that can I be comfortable, even when the points a manifesto makes, taken one by one, are points I would endorse. A la rigueur, a Dadaist screed might be acceptable to my jumpy stomach.

Wanting to assemble a set of responses to the PEN Translation Manifesto for a journal, a couple of bright young things wrote to solicit a manuscript from me. I sent something outlining a particular position on translating and translation ethics that happens to be mine (a wholly empirical, quasi-autobiographical bit of writing). They replied at first with a commented version that raised “issues” about almost every sentence. I rewrote with a narrower focus. Here’s the second version.

Amicus Curiae, or the Niche Translator

HS, University of ***

I should begin by saying that I am not a full-time or professional translator, so the “Translation Manifesto” does not quite speak for me; conversely, readers of the “Manifesto” may find my experience irrelevant or trivial. I have translated when the spirit has moved me, out of admiration, and not for pay. In most cases my translations have emerged from friendships. That fact influences how I understand translation. For friendship is a singular, accidental thing, resistant to explanation. It comes down to chance, affinity, mood, and other indefinables. “Parce que c’était lui, parce que c’était moi,” as Montaigne put it (“because it was he, because it was me”). So too with translating. Unlike diplomatic, political, or business alliances, a friendship, or the quasi-friendship I am calling the translatorship, is not circumscribed by definite goals. Moreover, it is individual, not categorical. I have participated in translation projects that took a category and a goal—for example, retrieving pre-1911 Chinese women poets from oblivion—as their starting point, but for my translations to be at all convincing, the original had to have something that spoke to me.

The overlap between friendship and translating might be characterized with Seneca’s phrase “alter ego”: in translating you speak for another and as another. An ethical ideal, I would say, regulates both kinds of relation. Friendships (I am going to make some normative assertions here) are freely consented, not commanded. They require commitment. The person you are proposing to befriend or translate is another self with autonomous interests and will inevitably tax your patience as disagreements and personality differences emerge. At some point you may have to explain yourself to others (“How could you possibly have that person as a friend?”; “What made you choose to translate that author?”). In looking back over my translatorships, I would say that the “alter ego” status is not one that was given in advance, but one that I grew into or took on progressively as the work went forward. Friendships are consolidated by doing things together. It’s admittedly a strange thing to say that a sixteenth-century Chinese poet and I were “doing things together,” but in some sense we were.

The analogy with friendship helps me clarify how I approach translating, but I can also imagine situations where competent and ethical translators would translate texts with which they feel completely at odds. Is hate-translating a counterexample to my analogy? Not necessarily; in such a case the translator is acting as friend and advocate for a forum, serving that forum best by translating as accurately as possible the hated content. The collectivity of people who are opposed to anti-immigrant bias, for example, will be well served by knowing exactly what politicians and ideologues say in this or that language to stoke up anger against foreigners. A translator can’t be blamed for making that information available.

Continuing, however, to explore translation’s overlaps with friendship, I observe that “friends possess things in common” (Plato, Phaedrus 279c). I don’t charge friends to eat at my table, and I consider it good fortune to have something to share. Friendship operates in a gift economy, not an economy of exchange. The “Manifesto” calls on us “to be transparent about rates and terms, to not undercut colleagues in the field, and to engage in open conversations about unpaid work. … Translators of literary or other humanistic texts based at universities must be cognizant of the effects of their university employment on independent translators’ livelihoods.” Well then, for the sake of transparency and “open conversations” let me put it on the record that as a senior academic at a prominent US university, I can translate without concern for payment or promotion. Some would call that privilege. I won’t shrink from the word. By producing English versions of Chinese philosophy, Haitian poetry, or Sicilian drama, I’m not undercutting other professional translators who would need to be paid to do the same; it’s rather the case that if I don’t do it out of the resources of my privilege, the job may not get done at all. My Haitian poetry translations had to wait thirty years—until I had stored up a lot of titles and prestige—before a publisher would consider them. Getting Li Zhi, Jean Métellus, or Tino Caspanello published in English was worth doing, even if it involved less than perfectly egalitarian methods and netted negligible rewards for author or translator. I would go so far as to say that translators like me use private means to produce a public good.

Few publishers are committed to literary translation. Much of it must then be produced in something like a gift economy, with overt or tacit subventions. (My drug of choice is poetry, a commodity for which marketability and quality observe a generally inverse correlation.) That the profit-oriented business model skews the supply of translations is obvious, but I can well conceive that the accumulation of pet projects and labors of love would distort it too. What is the best way to build a lively, diverse, surprising culture of translation into English? Can we translators create a demand for our work, and thus be perceived as a source of market value? Now and again a small publisher of literary translation issues a book (better yet, the first book in a series) that is taken up by one of the behemoths of publishing and becomes a hot property, perhaps even the symbol of a trend (Nordic crime fiction, for example). The small publisher and, one hopes, the translator both benefit; the big publisher benefits much more; the English-language readership wins as well. But these are exceptional cases. In many other language-domains it is taken for granted that works in translation interest a broad public and are therefore valuable.

The “Manifesto” acknowledges the complexity of the translation market by issuing a stream of critiques, recommendations, and demands that touch on different points of the production chain—so many directives and so many points that one can’t help wondering if they are all compatible with one another or with the conditions of their possible realization. The “Manifesto” calls on publishers and institutions to honor their “responsibilities.” There’s ethical language again—in a legal, political or contractual idiom. But in an economy or ecosystem with many independently moving parts, it’s hard to say where responsibility resides. Say the onus of the recommendations is to fall on editors: they do have the power to approve projects and sign contracts. But they are nervous polar bears on melting ice floes, just like authors and translators. For-profit and academic publishers alike occupy niches in a tremendously concentrated ownership environment in which choices made by the biggest participants dictate the conditions of the smaller ones’ survival, and book publishing must vie with omnipresent digital content that is, if not acquired for nothing, often given away for nothing in pursuit of audience share. The above are durable, structural obstacles in the way of building a culture of translation in the English-speaking world. What leverage can be wielded by translators trying to make a living in that environment? The “PEN Translation Manifesto” is one attempt to use reputation and codes of behavior to even out the unequal rewards doled out to translators who translate from different languages, from different backgrounds, in different genres. If publishers pay attention, wonderful; but I suspect they will continue on their preset path, departing from it only to avoid financial loss, boycotting and scandal.

In the United States, the non-profit sector of universities and foundations may be badgered into providing greater support for translation. Relying on the public sector is probably unwise at a cultural moment that has seen so many laws passed against education and reading (I see you, Florida, Tennessee, Texas, and the rest). The time may be past when we could assume that all members of a free society were “friends,” insofar as they agreed to coexist and support one another’s right to the pursuit of happiness. Indeed, even the foundations and universities have shown themselves weak in the face of illiberal outcry. A polarized society makes everyone in it more ignorant and less curious. Literary translators have the thankless task of resisting the pressure of commercial balance-sheets, which is bad enough, but not nearly as harmful for culture as the pressure of ideological balance-sheets, where scoring points and neutralizing imaginary opponents is the order of the day. The governor of Florida is aware of Judy Blume and Mickey Mouse; just imagine what will happen when he learns of Constantin Cavafy, Clarice Lispector, and Wang Anyi.

The “Translation Manifesto” strengthens my admiration for those translators who are carrying out a struggle on economic, political and cultural planes, all the while holding themselves to the standards of their art. I can only hope that the efforts of people like me, insulated to some extent from the indifference of the market and the hostility of the mob, will be seen as supportive and not “undercutting.”

After receiving the above, the Bright Young Things responded: “We’ve looked over the revised draft carefully and after a lot of thought and consideration, we have decided not to move ahead with production on this piece. We feel that it still has some significant structural issues and resolving them would stretch our team’s capacity and make it impossible to meet our production deadline at the end of this week. Not to mention, that it would demand more of your time.”

Okay. “Significant structural issues” means, I suppose, that I spoke individually, and that I wasn’t an individual they were interested in hearing from. (They have got the bureaucratic tone down to a T, though.) No big deal. You can’t please everybody.

Some more reflections now about translation’s place within anglophone culture, with ref to PEN’s storied history.

One of the most significant moves of the PEN “2023 Manifesto on Literary Translation” is to posit translators as authors. Not as monadic, solitary geniuses (that sort of claim never really applied to “sole” authors anyway), but as authors of “a set of interpretive relations with an existing text.” Those intertextual relations stretch out into another domain of relations, that which connects with publics. From their position between a text and its publics, translators open some kinds of connection and foreclose others. I agree, of course, with this understanding of translation.

To illustrate the point, let me turn back to the author of the first PEN translation manifesto, Robert Payne in 1963. Payne’s name will be familiar to members of my tribe—devotees of Chinese poetry—for The White Pony, an anthology he edited in 1947. In that book’s introduction Payne laid out the case for the value of Chinese poetry to English-language readers as it could best be stated in the immediate postwar period.

We may regret that Chinese poetry is eternally changing, but like the Chinese earth itself, we know that it is eternally the same…. There are times when China cannot be understood—there are permanent barriers that cannot be forced—but there are other times when a line of poetry, a single stroke of a brush on a sheet of silk, or perhaps some song sung by a girl in a rice field will tell us more than we have ever learned from books…. Chinese poetry does not change with the times…. Here is poetry, clear, concise, etched sharply on the clear minds of the people and written in those characters that more than any alphabet conspire to make the word read the same as the thing seen, the emotion experienced, the thought made luminous. … We who are constantly changing, at the mercy of every influx of scientific ideas, may do well to ponder sometimes the poetry of these people who are as unchanging as the stars.[1]

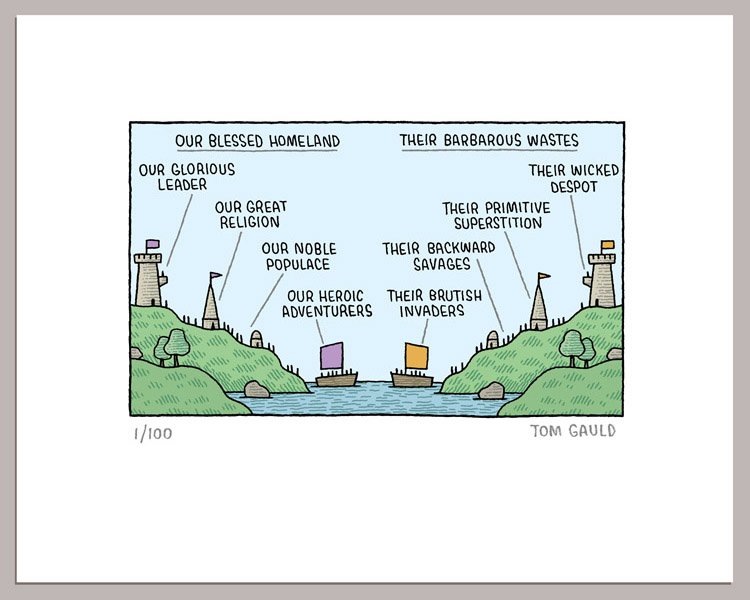

Encountering this, I cannot help recoiling: is this not the purest expression of “the tendency to essentialize cultures and languages,” the very “cultural erasure and the fetishization of difference” that the 2023 Manifesto denounces (and justly so)? But I am also reluctant to set my foot on the trunk of the defeated dragon of essentialism, partly because I cannot be sure it is dead, partly because the awareness of the translator (or editor) as weaver of relations with a public makes me ask: what exactly was the most effective way, in 1947, to secure a wide English-language readership for a complex, demanding artform from long ago and far away? Adopting the verbal tics of what would later be called “Orientalism,” not to bury China but to praise it, was the strategy that occurred to Payne, who nonetheless, as a personal matter, clearly wanted the best for Chinese poets and their translators. It is not enough to say that Payne was wrong or tainted by colonial thinking. He was doing what translators do– making connections– though not as we would do it, as he was doing it in a world that is no longer our own. With this example in mind I hesitate to fall in with the peremptory tone characteristic of manifestos, including PEN’s 2023 one.

The problem of knowing who is on the right side of history arises here and there when the Manifesto rises from economics to morality. The Manifesto’s authors protest “tokenization” and judge that “the tendency to mask inequities via gestures such as awarding prizes and raising awareness about underrepresented authors is endemic to the publishing industry”; but without a generally received criterion of sincerity or mercenariness, or better yet concrete instances submitted to debate, these are vague directives to be applied in keeping with a criterion of “if you know, you know.” If we are going to accuse whole professions of complicity with evil (“There has yet to be a full reckoning with the role played by translators—including literary translators—in genocide, colonization, and enslavement, all of which continue to influence how the field operates today”), let’s see some specifics, both of what should be done and what should never be done again.[2]

The Manifesto is right to recognize translators as authors. But what that means is, as always, subject to conditions. It is as if a voice had said, “Partake of this theory, and ye shall be as authors.” To be an author in the twenty-first century is not what it was in the era of the author as hero, nor again what it was in that of the death of the author. Ours is the era of the flattening of the author into sociological categories. Publishers expect me to be interested in a poet or novelist because of his, her, or their race, nationality, or other status. Henceforth, translators will undergo the same labeling. But I’m not sure the art of translation gains much from being made relative to the identity of the translator. Translation seems to me to have to do with connections rather than identities, with others rather than selves. I would find it dreadfully patronizing to see my work announced as that of “a white male American translator of Chinese poetry,” though if you care about labeling me you are free to look up my picture and demographics. In this regard I try to do unto others as I would have them do unto me, ignoring the labels in favor of the actual work. And if I may use one of the Manifesto’s concerns to critique another concern, essentializing the translator’s group identity is not much different from essentializing the cultural provenance of the text being translated— it is once more a case of “the fetishization of difference” executing “cultural erasure.” I would rather have readers stress the translator’s agency—the power to imagine, decide, and do.

[1] Robert Payne, “Introduction,” in Robert Payne, ed., The White Pony: An Anthology of Chinese Poetry from the Earliest Times to the Present Day, Newly Translated (New York: John Day, 1947), xii, xv, xxv, xxvi.

[2] For a study of specific cases in this area, see Tiphaine Samoyault, Traduction et violence (Paris: Seuil, 2020).