Larry McMurtry already wrote about “Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen,” but that was science fiction or cultural collage. Walter Benjamin in Music City, USA? Only a step or two, or a misfiled letter, away from being reality! Let me take you down the relevant arcade, or passage.

Imagine: Walter Benjamin, the chronicler of the Parisian arcades, those glass-ceilinged shopping domes and forerunners of yet grander commercial utopias to come, would have had the chance to pace up and down in this little channel between two Nashville streets, where, in my teenage years, you could buy popcorn, sheet music, and rubber stamps. Would have, that is, if he had not killed himself with an overdose of sleeping pills on his way over the Pyrenees in September 1940, on hearing that his group would be refused entry to Spain and forced back into occupied France, and most likely sent from there to a camp.

I have long dreamt of alternative futures for Walter B. I’ve imagined him a rewrite man in Hollywood, assigned to keep track of the notoriously unreliable William Faulkner. Or a lowly inventor of gags for Walt Disney’s weekly comics. But I had never imagined the possible and nearly realized future for Europe’s most rueful Astyanax that jumped off the page last night with all the irrelevance of a Buster Keaton plot line.

Benjamin left a lot of correspondence– six volumes in the Suhrkamp edition. I’ve never even tried to read them, putting that off for the day when I have a better knowledge of the man’s writings for the public (and, since we’re talking about hopes, when my German is quicker and more precise). Some of those letters are in French, however, and that gave a publisher the idea of making a smaller collection of Walt’s Lettres françaises (Paris: Nous, 2013). The excellent introduction is by Christophe David.

While Benjamin was fretting away in Paris, trying (but not too hard, because he was a consummate gentleman and a consummate procrastinator) to pull some strings to get away before the German occupiers caught up with him, and counting, as the rest of us have heard, on his friends Horkheimer and Adorno to find him some means of passage to the States, another possibility of escape arose. This was good, because from all evidence, Horkheimer and Adorno appear to have given little thought to saving their impractical friend. The other path was opened by a woman named Cecilia Razovsky, who ran an organization called the National Refugee Service. The NRS sought out American sponsors for European intellectuals in danger (largely Jewish, as goes without saying). The sponsor they found for Walter Benjamin was a poet and psychiatrist from Nashville, Tennessee, residing in Boston, named Merrill Moore.

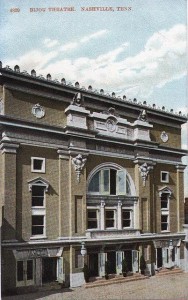

To guarantee that the entry visa would be taken seriously, a job had to be promised to the potential immigrant. Moore’s only employee was his secretary. But Moore had a friend, Milton Starr, whose father, Alfred Starr, had been like Moore (and John Crowe Ransom, Allen Tate, Robert Penn Warren, Donald Davidson, etc.) a member of the “Fugitive” group of Southern poets. And Milton Starr was at home with money: Moore had already enlisted him as banker and trustee for one of Moore’s patients (and son of his secretary), the future poet Robert Lowell, whose pecuniary dealings with his family were so emotionally complicated that it was easier to route every check through a stranger in Nashville.* Starr was part owner of the Bijou Theatre in Nashville, and it was in this capacity that he filed an affidavit with the National Refugee Service promising employment for Dr. Walter Benjamin on his arrival in the US.

The Bijou catered to a “negro” clientele, in the parlance of the day. Bessie Smith sang there once. Milton Starr headed an organization, the Theatre Owners Booking Association, that signed blues and vaudeville acts for tours throughout the South. I can well imagine Walter Benjamin, having left in Europe his briefcase crammed with notes on all the ephemera and trivia of nineteenth-century Paris gleaned by sitting over a decade in the Bibliothèque Nationale, becoming an expert on the chitlin circuit at the side of Milton Starr: arranging contracts for Blind Willie McTell, running down to the alley for a little cocaine to go in Ma Rainey’s pre-show pick-me-up, correcting the proofs of a poster from Hatch Show Print. The Bijou was exactly half a block, around the corner, from the Arcade.

It was not to be. A mixup in the American consulate of Bordeaux (they had received Milton Starr’s documents but had no record of Benjamin’s ever applying for a visa– and perhaps he hadn’t got round to it) and the confusion of Benjamin’s several pending schemes for emigration– to New York, to Cuba, to the Dominican Republic, to Argentina– resulted in his taking the less advisable footpath route over the mountains to Port Bou, and thence to his death. It was a slow, horrible death by self-poisoning in a hotel room with the police tramping up and down the corridor.

The founder of the Fugitive, Sidney Metatron Hirsch, never explained what he meant by the magazine’s title. Allen Tate guessed that “a Fugitive was quite simply a Poet: the Wanderer, or even the Wandering Jew, the Outcast, the man who carries the secret wisdom around the world.”** I think Nashville was waiting for Walter Benjamin to explain it to them.

(Christophe David, “L’envers de l’histoire contemporaine, ou rêveries sur les vies parallèles et croisées de quelques femmes et hommes de lettres illustres ou non à partir des lettres que Walter Benjamin écrivit en français,” in Benjamin, Lettres françaises, pp. 7-77.)

* Also at Moore’s urging, Milton Starr had bankrolled several years of the psychoanalytic journal American Imago and successfully brought Moore’s control analyst, Dr. Hanns Sachs, out of Europe.

** Cited, Louise Cowan, The Fugitive Group: A Literary History (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1959), p. 35.