Some people think MOOCs are bad, some people think they’re good (though I know almost none of the latter). But what you really need to know is: what’s going to happen to the university in the next twenty years as a result of innovations in content delivery?

Some people think MOOCs are bad, some people think they’re good (though I know almost none of the latter). But what you really need to know is: what’s going to happen to the university in the next twenty years as a result of innovations in content delivery?

Luckily for you I have had a vision of the future. I don’t like some of it, but I think it’s accurate. If I were a dean or a university or college president I would be thinking about what I could do right now to respond to the changes that are coming. And if you teach in a university, or attend one, or plan on having friends or children who do, then you need to know what’s coming, because it will affect (and indeed transform) the entire institutional structure of higher education in the United States (and probably worldwide). I’ve put it all in an eay-to-read Q&A format, so no excuses for not following along.

As a bonus at the end I’ll tell you what’s happening to public education at the K-12 level, and offer some suggestions on how to keep the most disastrous vision of the future from coming true.

Q: Are MOOCs going to change the college/university system?

A: No. The system exists partly as an educational tool, but also as a credentialing mechanism. Until MOOCs are offered for credit, they are essentially the equivalent of books or those eight-CD “History of Jazz” sets you could listen to in the car. The revolution in higher education will happen when universities start offering MOOCs for credit, allowing them to become MOCCs: massive online courses for credit. When that happens everything will change.

Q: Why?

A: Right now there are about 4,100 universities and colleges (including two-year colleges) in the United States. You can figure that most of these places have at least one person who teaches advanced algebra. In twenty years there will be maybe 200-400 left, because if someone figures out how to do a MOCC for advanced algebra, there will be absolutely no reason for many universities to offer their own courses. A good MOCC is like a good textbook. You don’t need 4,000 textbooks; you need four or five.

Q: So why will you still need 200-400 people?

A: Because education with humans will be offered at a premium cost point. We all believe (and I think it’s true) that education with humans in a classroom is better than online learning. People who can afford it will still send their children to schools with human teachers. The elite small liberal arts colleges will probably come through this revolution largely unscathed; so will the top private universities. I’m guessing that there are 200-400 of those around. Maybe it’s fewer.

Q: Will everyone else be educated by MOCCs?

A: Yes and no. You can predict that there will be an entire hierarchy of human involvement, setting up tranches designed to market and offer courses to the maximum number of people at the maximum number of efficient price points. So for instance the cheapest possible offering will be a MOCC with completely automated grading and crowdsourced discussion. Slightly above that you might have moderated discussion, or even live online chat (which is now offered for language learners by companies like Rosetta Stone); for grading you might have human-graded essay exams, or even human-graded writing assignments, with human feedback. (I do not believe that writing assignments will be machine-graded in the near-future.) Obviously “live” versions of any of this will cost more than online ones, and synchronous ones more than asynchronous ones.

At that point you can basically imagine that the cheapest offering will be the all-automated MOCC, and the most expensive one will be the algebra seminar with 15 students offered by a full professor. Costs will array themselves accordingly.

Q: Which courses are most likely to end up as MOCCs?

A: Anything that is being taught now as a large lecture with little or no discussion and machine-graded exams will become a MOCC in the next five to ten years (Alexander Halavais agrees). This includes a huge variety of general education courses at public universities, from the humanities to the sciences and everything in between. Similarly anything that has exams that can be largely machine-graded risks becoming a MOCC sooner rather than later. I don’t know much about accounting, but I am guessing that much of an accounting degree could be placed online, for instance.

Q: Which courses will be immune to that pressure?

A: Courses with labs will be able to resist, especially if the labs involve the manipulation of objects. And any course with a significant feedback-based writing component will be able to resist, because there is simply no way to provide the feedback you need to teach writing without human interaction. Speaking of human interaction, any course that involves a performative element requiring the presence of others—courses in public speech or acting, or, say, nursing or physical therapy—will be hard to make into MOCCs. Finally, courses that have a “critical thinking” component that involves dialogue and debate will also be able to resist the trend. But no course will be immune.

Q: Why not?

A: Because you can MOCC components of a course, even if you cannot put the whole thing online. For instance you could put large chunks of a nursing course (the parts currently covered by the textbook and lectures) online, and leave the rest to human practicum. With science labs, you can create virtual spaces in which students could, for instance, mix chemicals or perform experiments with virtual objects coded to react like their real counterparts. Basically, if your course has a textbook, it can be MOCCed, and the mock version will work enough like the real version to make it offerable for credit. And even if it doesn’t have a textbook, if it has components that can be structured as lectures (for instance on “the history of the English novel” or “Shakespeare”), especially if those lectures can be supplemented with online audio/images/video, then portions of that course can end up online for credit. At the far end you can imagine that some portion of nearly every course in the institution could be online. And the end result of that is that you need many fewer teachers than you have now to teach the same amount of students.

(I do think, incidentally, that the liberal arts, which involve so much discussion and writing, are poised to better weather this change than most other fields. Which feels weird because I’m accustomed to writing things like, “this will be bad for the universities, but especially for the liberal arts.” Not this time, suckers!)

Q: So there will be fewer teachers.

A: Yes, across the country and probably worldwide. Easily MOCCed courses will require probably only a handful of versions. It’s like what happens with the invention of recorded music: before that every village has its own singer. Once you get recorded music all the singers who were the best in their villages but not that good (or lucky) within the larger group of singers nationwide are out of work. And if for instance some village happens to be the capital city (i.e. Harvard, MIT, Stanford) then prestige effects will mean that second-rate singers from that village may beat out first-rate singers from smaller less prestigious villages to become the makers of the recordings that everyone listens to.

Q: That sounds a lot like what’s happening now.

A: Yes.

Q: And what happens to universities once the faculty are removed?

A: Well, let’s be clear. A lot of the folks who will be out of work will be the lecturers and adjuncts who currently teach General Education courses at large universities. I honestly think that market and field will be decimated by these changes; I just don’t see how such people will keep their jobs in the long run. I can certainly imagine some of those jobs changing, so that instead of teaching three or four sections of World History on your own, you do discussion sections of the World History MOCC your institution uses for 12 or 14 hours a week. But again, a place that has ten or fifteen people teaching World History courses might end up needing only three or four, if two-thirds of the course hours end up online. Similarly for any other Gen Ed offering.

As for the tenure-line faculty, of course, they’re vulnerable too. I taught World Civilization at the University of Northern Iowa; I have no idea how long it would take a school like that (Research 2, 3/3 teaching load) to sign up for MOCCs but I am sure some of them will be trying it soon, as is, for instance, San Jose State (another Research 2).

My pessimistic guess at this point is that you could pretty easily see a one-third or more reduction in the total number of tenure-line faculty nationally, especially if you figure the effects of these changes on PhD programs, which I’ll get to later.

Q: What about the big public Research I institutions?

A: They’re in trouble too. To understand why you have to understand that MOCCs will end up being VERY NEAR to free. All the costs are upfront; presumably there are some maintenance costs, and I can imagine textbook companies will try to capture some of these costs and to charge more for various online services (so that for instance some unemployed adjuncts might end up working for Pearson, getting paid by the hour to do discussion sections). But allowing MOCCs to be captured by the for-profit education industry would be the worst thing that could possibly happen, because it will bring us all the disastrous changes of the MOCCs without any of the benefits. And there are benefits, though they will come as very small consolation to the professions that will find themselves devastated by the coming changes.

Q: Why will (or should) MOCCs be free?

A: Look. The internet is absolute full of amazing free stuff that people put up online. Do you think that the MOCCs will be any different?

Q: But they will have to be issued by an appropriate authority!

A: Yes, true; no one’s going to offer credit for my homemade MOCC on nosepicking. But I am hoping that places like Harvard and Stanford will end up creating and sharing these MOCCs for as little as it costs them to make them. If they don’t, it doesn’t matter, because some university somewhere will. And sure, maybe you’d pay more for the Harvard algebra course than the Bucknell one, but if the Bucknell (or some other do-gooder institution) course is closer to free, and you get the same amount of college credit for it, then…

It’s absolutely crucial that this happen because otherwise what will happen is that the textbook industry, which gives chicken-fucking a good name, will take over. So even though in many respects a near-free proliferation of prestigious MOCCs will make the institutional transitions worse than they might otherwise be (see why below), without them we’ll simply end out outsourcing our educational system to private, for-profit corporations, which will squeeze their profits out of vulnerable students and their families (and indirectly the federal government student loan programs).

Q: How so?

A: If the for-profit industry takes this over, then essentially what they’ll do is try to establish a semi-monopoly (think oil industry) on the delivery of the educational product, then use that position to extract profits from the vulnerable. Even in a competitive market, as we’ve seen in health care, for-profit institutions use up a much larger of their budget on “administrative costs” than non-profits.

So the best-case scenario is for the MOCC industry to be as non-profit as possible, as committed as possible to delivering the cheapest possible courses while maintaining high levels of prestige. If the top universities don’t do this (and I think they will) then hopefully some well-meaning billionaire will (I’m looking at you, Soros!).

Q: OK, so the courses are close to free. What happens then?

A: Here’s what’s going to happen. I am 18, thinking about going to Penn State. But even in-state it costs $15,000 a year. That’s a lot of money. Then I do some poking around online, and I realize that I can get one-third of my degree via MOCCs from accredited institutions, for much less money. And Penn State has to take the credits for transfer, because it has agreed to transfer credits from accredited universities. (Or if it doesn’t—if it tries to implement some crazy MOCC exception—then I don’t go to Penn State, and I go to some other university that does.) So all of a sudden Penn State loses two or three semesters of tuition. This already happens, when students go to community colleges in order to save money. But now anyone can do this, from anywhere.

And of course since it’s online there’s no reason why I should do my MOCC at, say, one of the CUNY schools (which have to charge more because they have high fixed costs due to location), when I can do it at Truman State University, which charges less for the same thing. (Again: if they’re offering different things, if CUNY offers live discussion and Truman doesn’t, that’s a different story; the comparisons here are apples to apples.) And no reason to do the course at Truman if New Mexico State offers it for even less. And so on. Pretty soon a competitive market will drive the cost of the barebones, all-automated MOCC, to something close to zero. And that is amazing and wonderful news for students everywhere, even if it’s going to destroy any number of universities.

Q: Why is it amazing for students?

A: Two reasons: (1) Cost. (2) Access. Cost: if I need a college degree to get a job (and to become educated) and I can get the same educational experience and credit for less, then I have less debt and more money to spend on other things. Access: if I don’t live near a college I can now do much (if not, ultimately, all) of a degree online, with access to some very high-quality course material. This is great news not only for people in the United States but people beyond it.

Q: But aren’t MOCCs going to be of terrible educational quality?

A: Yes, and no. At some level they’ll be good enough. Students in a MOCC can be reasonably sure (because Harvard or Princeton or whatever is on the name, because the faculty member is a full professor who’s an expert in his/her field, because s/he has been selected because s/he’s a reasonably charismatic and compelling lecturer, and because $50-$100,000 has been spent on course development and testing, so the ancillary structures—the other material, the activities, etc.—are good) that the educational product they’re consuming is not full of shit. It’s like what happened with Olive Garden. People in my social class complain about the food, but it’s a hell of a lot better eating than you could find in the average Italian restaurant in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s. Olive Garden raises the bottom of the range of eating possibilities—you know it’s not going to be great, but it’s not going to be disgusting or terrible either. You lose, to be sure, the idiosyncrasies of the mom & pop place you used to go to, but I think the history of the world economy the last forty years has demonstrated pretty conclusively that local charm is the kind of consumer good only appreciated by people who can afford it. As a result local charm (in food as in education) will become a prestige product, as wealthy families continue to splurge on sending their kids to Colby or wherever.

Of course it would often be better to be in a room with people. But again we’ll see a multi-tiered system where people buy the education that makes sense to them, at the price they can afford. We have a system like that now, of course. But this will make the variety of options much more widely available, and it will make them much cheaper.

Q: So what happens to colleges and universities when all this happens?

A: Well, some of them are going to die. I don’t really see that we will need 4,000 different places when the internet makes MOCC and online courses widely available. But more specifically, you might ask: what’s going to happen to your university when it loses 20 percent (or whatever) of its tuition revenue, especially when that revenue is coming from the courses with the highest enrollments and, often, the cheapest labor costs? It won’t be enough to cut the teachers, since with large-enrollment courses, labor is pretty minimal. (For instance imagine a Gen Ed course at, say, Penn State, with 300 students, where the instructor is a full-time lecturer getting paid $50,000/year [pretty good in my field] to teach six courses. Instructor total cost per year is $65,000 including benefits, which amounts to $10,833 per course. Your tuition revenue is about $1,500 per student, assuming they’re all in-state ($15,000/year for 30 credits = $500 per credit; some take more but since I’m counting them all as in-state I’ll leave it be). That’s $450,000 in tuition revenue, out of which you have to pay the instructor, and then cover your administrative and building costs. (But of course your admin and building costs are more or less fixed—you have to heat/cool the building no matter what). So… now imagine that half of those students sign up for the MOCC version of the course at one place or another, because it’s so much cheaper.

At that point you might as well offer the damn thing yourself, and try to recapture some of their tuition by offering an in-class discussion section of the course on campus, or something. I could see, for instance, a student paying $100 more for the Penn State version of the Coursera algebra MOCC (instead of somewhere else’s essentially identical course) because s/he’s here on campus anyway, or trusts the brand, or something.

Q: So what’s going to happen?

A: Well, lots of people are going to lose their jobs. In the administration too; you may not need all those deans and associate deans and staff members once you’re doing less in-person advising, etc. And some buildings won’t get built, or renovated. And colleges will compete more than they now do on what you might think of as “amenities,” which will include not only the rock-climbing wall in the gym and dances in the student union, but also a variety of educational amenities, like human contact and discussion. Again, some of this is already happening now. But MOCCs will intensify the contradictions, as the Marxists used to say.

Q: But the private research Is and the prestigious SLACs will escape scot-free?

A: No. I have no idea where the line will be drawn, which SLACs will survive mostly as-is and which will have to radically change; which public universities will be able to manage the transition and which will struggle. Among other things it’ll depend on leadership, luck, and location. My guess is that the top 50 SLACs will be more or less fine. Beyond that I’m less sure.

Q: And the private research Is?

A: Anyone with a PhD program is going to be devastated by this. If your PhD program has placed anyone in the past decade into a less prestigious SLAC or a public university of any kind—well, that placement may no longer happen. If you mainly place to those kinds of schools… Well… my guess is that many PhD programs will contract by half. That means that if you admit fewer than six students a year you’ll either be shut down or collapsed into a broader PhD, because three students a year makes it nearly impossible to run a viable PhD program. Again, this has already happened at many places, which end up offering a “Literature” PhD to the students who might have ended up formerly in French, Chinese, Spanish, Comp Lit, and so on; except that the total number of PhD students will go from 20 across all programs to 10 in the new one. But it will happen more and more.

And even the top private research schools will contract, because I also believe that the effects of the loss of Gen Ed tuition revenue on the top public universities will be to scale down their faculty. I could easily see 20 to 30 percent contractions, or more, at the top private schools.

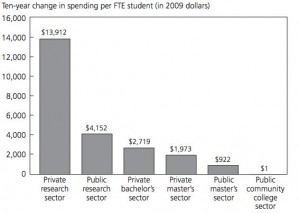

(By the way, why I am so sharply distinguishing the fate of the public and private universities? Well, look at the chart below:

What this represents (via Yglesias) is the fact that, during an era of declining federal and state revenues, universities are nonetheless spending substantially more per student than they were 10 years ago. They have gotten the money by raising tuition—essentially allowing state cuts to trickle down to families (and then in some cases back to the federal government via student loan programs). But the shocking difference here should come when you compare the first two bars. That’s per student spending! So if you think that the fate of the publics and the privates will be anything alike, I think you’re making a mistake.)

These contractions will have all kinds of impacts on the way the tenured and untenured faculty live and teach. Focusing on the PhD programs alone, they will among other things encourage more emphasis on undergraduate teaching, since there will be fewer PhD students to mentor and fewer graduate courses to teach. We might see some programs splitting (as they occasionally have in the past) into a “graduate faculty” and an “undergraduate faculty,” with the more prestigious former doing all the grad teaching. We may see more of a premium on the creative and engaged teaching of undergraduates, as universities will have to compete on the quality of their undergraduate education for tuition dollars. (This latter is not a bad thing.)

Q: This all sounds terrible to me. I love universities, I love education, and have given my whole life to it. I hate the idea that it’s going to be destroyed like this.

A: I hear you. I love this thing too. But a vision’s a vision. I am trying to think of all this holistically, to separate myself from the idea that this change is bad, or inherently bad, because it involves so many of the pedagogical panaceas I’ve been suspicious about, and because it is going to hurt so many people and institutions I care about. I am also really depressed when I think about the people who are going to enjoy this, namely the right-wingers who will be happy to see fewer professors in the world, and of course all the other people who hate education and learning, and who will be filled with schadenfreude as this wave comes down over us.

Q: Is there anything we can do to stave this off or save ourselves?

A: I don’t think so. I sympathize with the philosophers at San Jose State who resisted the justice MOOC, as I do with Haun’s call for great thinkers and teachers like Gregory Nagy to withhold their consent and participation from this entire endeavor. I in fact have danced around that position myself. But I just don’t think it’s going to do anyone any good. (Also, Olga is right in her comment on Haun’s post that some people are using MOOCs to destroy the university as part of a general assault on democracy.)

From a more institutional perspective, I can imagine a variety of strategies deans and presidents might take to try to capture as much MOCC revenue as possible; I can also imagine beginning to preemptively downsize a variety of programs. I think probably the best two active things an institution might do would be to (1) become a generator of high-quality MOCCs, and begin offering them at home; and (2) to figure out how to become a distributor of high-quality MOCCs at a variety of tranches, so as to maximize future revenue. It will be easier to do #2 than #1; but #2 is in some respects more complicated, since it involves coming up with good plans for online synchronous and asynchronous course offerings, as well as automated/human options. Winter is coming: I would do this toot sweet.

Q: Any silver linings?

A: The big one is this: it will be genuinely better for society and the world if this process manages to bring down the cost of quality education, and open its access to more people. It sucks that many people are going to get damaged in the process, but the overall global force of good education being available more broadly and cheaply is a good thing, a life- and society-transforming thing.

That’s why we have to work, even in the deluge, to make sure that it happens. I know it’s tempting to try to hold back the tide, or to figure that you only have a decade or two to go, so you can just live out your life in the old mode. But if this thing is going to actually be good and go right, then it will be because people who really care about education (and its relationship to informed and engaged citizenship, to social life, to aesthetic and intellectual pleasure) get involved in making sure that it’s as free and as good as possible.

So… I am going to figure out how to do a MOCC in literature. I am not sure what or how yet. But I want to try to do this as best as I possibly can, to make this something I really believe in. I’m committed to trying for a few years. If I cannot manage it, then, good, I’ll know. Maybe someone else will (good news!), or maybe I’ll find out that it’s impossible. If so, I’ll despair, knowing that I participated in the instrument of my own degradation.

For now, however, optimism of the will. I am off, clear-eyed, to work.

***

p.s. I know I said I would say something about K-12 education but honestly this took a long time to write, so that will have to wait for later. In short, however: there the capture of the system by for-profit industries, and the willingness of politicians to participate in the destruction of common public education, has created a far more terrifying situation than the one we face.

Part of me wants to agree with this dark extrapolation. But I’m not sure it takes into account the other reasons 18-year-olds go to college (aside from earning a credential): to have social interactions with their peers in semi-freedom, to have adventures and mishaps in semi-safety, to mature. You predict especially dire times for public universities, but say nothing about the sports culture and social life that attracts many young people to them in spite of high tuition and student loans. Wouldn’t it be ironic if what prevents this dystopia are the very non-academic aspects of college that so many of us lament–sports and Greek life?!

The all-extracurricular model of the university has already been tried. Read “Stover at Yale” (1911). How we got out of it, I don’t know.

KSG, you may well be right… but that picture doesn’t seem any less dark than mine! It may well be that we get dystopia anyway, but with a fraction of the university budget that used to be spent on teaching now spent on the various social amenities (including sports) that are designed to make college a general “experience” for kids. You see the same thing happening with the rise of private housing for students… what they sell is the pool and the pool tables.

Pingback: Why deMOOCification won’t work « Lisa's (Online) Teaching Blog

No matter how noble your intentions (or any other faculty member’s) may be in offering a MOOC or MOCC, I think you’re fooling yourself if you think it can offer a high quality education, first and foremost because content delivery is NOT the same thing as an education. To compare the quality of a MOCC to an Olive Garden meal is to accept the pernicious idea that education is a consumable good like any other. Well-constructed, clear, charismatically delivered lectures can certainly be part of a good education, but what are students DOING with the material that’s being delivered via lectures? So far, the discussion forums on Coursera and edX are not terribly functional and don’t allow for sustained discussion. And without any facilitation by instructors or any feedback on students’ contributions, where’s the real learning? The quizzes and tests only test recall, NOT higher order cognitive skills.

Do I think quality online education where students learn deeply and retain what they learn is possible? Sure, but I don’t think MOOCs as currently conceived by the major players are it, and the way they’re selling it to state legislatures as the solution to the higher ed “crisis” as manufactured by various forces is not even close. So, your take seems to be, “we can’t beat ’em so might as well join ’em” so that you and the institution to which you belong can be on the right side of the evolutionary game. And who could blame you? Maybe you’ll find a way to build a mind-blowingly awesome MOCC that’ll change the paradigm, but in doing so, you’ll also be contributing to the destruction of an educational biodiversity whose value can’t be easily quantified.

@Soo: you open by saying that I’m fooling myself if I think MOCCs can offer a “high-quality education”; your evidence is the current MOOCs. But the word “Sure” in the second sentence of your second paragraph seems to suggest that you think a well-designed MOCC *could* deliver such an education, even though no examples of it exist (largely the fault, as you suggest, of the legislatures and the for-profit players). I don’t disagree with the second point — my argument isn’t that MOOCs are delivering high-quality educaiton, but that we ought to try to see if they can. (I have a secondary argument which is that a lot of existing education is quite shitty and so it doesn’t take much for something to be better than it — that is why/how MOOCs can resemble the Olive Garden).

In any case either you believe that there could be a “high-quality” MOCC that really teaches, or you don’t. If you don’t then this is an unmitigated disaster. My response in the face of that is to choose optimism of the will, not because I’m sure it’s right, but because it’s the only way I can live.

At the end of your comment you say that even if you do make a “mind-blowingly awesome MOCC” you’ll still be screwed because you’ll destroy the educational ecosystem. I agree that the value of the diversity of an ecosystem cannot be quantified, but, let’s be clear, the educational ecosystem differs from an actual ecosystem in one important respect: in it diversity is not necessarily a fundamental value. For instance you could not argue, or would not, that having a university sprinkled full of terrible teachers is useful because it “diversifies” the pedagogical system. (You might argue that having people with different teaching styles or points of view does–but my point is that diversity is not inherently good; we’re always talking about diversity of something; sometimes it’s good and sometimes not.) So at some level I think we have to think about what kinds of diversity we care about when we think about teaching.

To now argue your side of it for a bit: it makes me instinctively uncomfortable to imagine a world with only one or two US history textbooks. So I understand where you’re coming from. I guess I would want to think hard about what kinds of diversity are valuable in education in general.

I think most of the musings here are right or close to right. At this point in time. But things continue to slide about and adjust (e.g., Coursera now linking up with BlackBoard). So much is being done based on very soft data, and that is a huge problem. Esp when you get state legislatures and governors involved. I was at the recent one-year anniversary celebration of the establishment of the Office of Vice Provost for Online Education here at Stanford. Let me describe three main kinds of players. First there are the CS people who are delighted to have such a bright platform to show how their work can contribute to education. Second there are the School of Ed people who are delighted to have these amazing tools with which they believe they can solve all the problems plaguing education today, from learning issues to funding issues. The third group is more shady and hybrid–the latter-day avatars of Daphne Koller, Sebastian Thrun. They vary in their commitment to either of the above and right now are mostly concerned with the bottom lines and investment obligations of their new companies. The mood was nothing less than ecstatic.

The next week I took a long hike up Mt Tamalpais with Howard Rheingold, who has thought more about these things for longer than anyone, probably. Our consensus was that as long as the production of online ed is driven by a business model only interested in easily rolled-out, easy-to-imagine profitable products, the real potential of online is wasted. No time to incubate, experiment creatively, etc.. Furthermore, as Chris Newfield has pointed out, even the cost-efficiency of MOOCs is mostly a myth, and as companies like Coursera (and Udacity, Bogost argues) slide into for-profit (now who could have seen that?), things just get worse.

Finally, the assessment issue. We are not behaving even as semi-responsibly as the FDA, or any of the college-accreditation bodies out there that we are subjected to. There is not enough data to tell us if any of this works, or how. What are the “learning outcomes”? What “goals” are there? The same as those of the F2F courses they emulate? If it is skills-transfer, that’s one thing. but even people in the medical school here that I talk to, who have taught online, are dubious.

I am not at all necessarily against online ed. But we really do not know what it is, not enough to jump in line and take out our checkbooks quite so quickly.

Thanks for this, Eric.

Hey Eric,

Thanks for taking the time to respond. To take your points in order:

— I remain highly skeptical that even a well-designed MOCC could deliver a high-quality education. The massiveness and openness present real structural barriers to meaningful engagement and the whole thing would have to be radically rethought to allow for what I consider to be effective learning, especially at the undergraduate level, and by that point, is it a MOOC? I know there are fans of MOOCs and I’ve only sampled two, so my experience is limited, but I think the premises on which current MOOCs are designed are fundamentally flawed.

— Yep, there’s a lot of shitty education out there, so it’s true that it doesn’t take much to improve on it. But to focus all our creative energies on developing slightly less shitty versions of F2F education by basing online education on the shittier models (large anonymous lectures with no real accountability for student learning) and tweaking them seems like a misdirection of attention and resources if you’re really interested in quality online education. If you’re interested primarily in cost-cutting and efficiency, and disempowering faculty, that’s a different story. I’m willing to concede that well-designed online education that takes the best of F2F models and the best that technology has to offer is possible – our office is currently helping faculty at my school develop online versions of their courses, flip their courses and make them more blended, use the LMS to connect multi-section courses, etc. So, I recognize the value of technological tools in education. But of course, doing online education in a pedagogically thoughtful way takes a lot of resources and upfront investment. This kind of investment is precisely what the MOOC pushers want to avoid. What they’re investing in instead is potential markets. To me, there’s a difference.

— Here, I’ll add that if faculty members are no longer engaging directly with their students, and are not providing meaningful feedback on their work (even if mediated through graduate student assistants whom they train/mentor), then they’re not really teaching. They’re creating educational products, and so far, MOOC professors seem all too willing to cede authority over how those products are used and to what ends. I’m enjoying Sandel’s Justice course; he’s a masterful lecturer and I’m even learning some things, despite not doing much of the reading and no longer participating in the forums. But what a major disappointment it was to read his response to the San Jose open letter disavowing any knowledge of, and therefore responsibility for, how edX is planning to use its MOOCs. Really? Is that how Justice rolls?

— And why is running with MOOCs the only optimistic option here? Are MOOCs in fact the inevitability that everyone seems to take as a given? Isn’t there a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy feel to that whole thing?

— Yes, let’s talk about diversity in education. Diversity isn’t a fundamental value in education, but the diversity of learners (their abilities, preparation, motivations, aspirations, resources) is a fact. In my view, it would certainly be a disaster if people who wanted to pursue higher education didn’t have a diversity of options in trying to balance affordability and quality, if a student with limited resources didn’t have a local community college or public university, and had MOOCs as their only avenue of learning. The diversity of learning environments that MOOCs would choke off would, I fear, also choke off certain segments of learners who do not thrive in the MOOC system.

So my optimism of the will is to argue that there ARE and MUST BE other alternatives to affordable, quality education beyond MOOCs, and we have the research and the tools to build it if enough people (starting with faculty themselves) can be persuaded to expand their definition of education beyond the impoverished idea that knowledge can be packaged and consumed as morsels of content.

Ultimately, though, I don’t think ANY technology can be a substitute for face-to-face interaction, because teaching and learning are fundamentally social activities, and the sociality of the online environment is qualitatively different from the in-person. It’s great that you and I can have this rather heated debate on a topic we both have strong opinions about and stay connected over distance and time right here on a blog we conceived of and built together. But I’d rather be having the conversation in real time, in the same space, so I can convey without having to say it my general affection for you as a friend, even as I’m expressing my annoyance (hostility?) at your stance on this whole MOOC business.

My way into big problems is often to look at smaller issues and see how they develop into larger issues that might shed new light on the big problem. So: you write, “for grading you might have human-graded essay exams, or even human-graded writing assignments, with human feedback. (I do not believe that writing assignments will be machine-graded in the near-future.)” And therefore, “any course with a significant feedback-based writing component will be able to resist, because there is simply no way to provide the feedback you need to teach writing without human interaction.”

But is resistance futile? By which I mean, does something that stands outside the path of the juggernaut not just relegate itself to obsolescence by its stance outside the path of said juggernaut? In other words, if writing can resist the MOCC, and MOCCs are the unstoppable trend of the future, then won’t the trend of the MOCC also be to make writing not part of the MOCC purview, and therefore no longer a component of education? If the MOCC can only handle multiple-choice assessments, won’t all assessment become multiple choice?

This may be the most frightening aspect of the MOCC, that it will get rid of the teaching of writing–because I consider the teaching of writing essential to the teaching of critical thinking, and I consider critical thinking to be the real heart of education, why we who believe in it believe in it, and why those who oppose it or want to change it oppose it or want to change it.

For instance, my undergrad and MA students so far have a very hard time with writing. (There are some caveats here, such as that not one of them has been a native speaker of English, and of course what counts as “good” writing will vary from culture to culture, but of course we here have all had the experience of recognizing good writing even or especially when it comes from a culture not our own, and when I say they have a hard time with writing I’m talking about how they structure their arguments rather than about whether they have problems of syntax or word choice.) I’ve got to believe that they have a hard time with writing because they haven’t been trained in it before coming to university, that they’ve been trained in a system that values the kind of thinking that can be assessed on multiple choice tests. And a system that values this kind of thinking, to put it as charitably as I can, is simply not the kind of thinking that I value.

I would really like to see more of your thoughts on K – 12 education, then, because it does seem very relevant to the changes that take place, that will take place, or that can take place in higher education. I have the sense that writing is already undervalued in K – 12 education in the US (I do not believe that “teach to the test” allows much room for education in writing), and suspect that the “inevitable” future of MOCCs in higher ed. means that writing will end up even less valued in primary and secondary education. If this is so, there are great and disastrous consequences to consider, if you believe as I do that the education in writing is so fundamental to an education in thinking.

Lucas