The Plural of Truth is Treeth

h.saussy

I don’t know how the whole herd immunity thing is going, and a vaccine against covid-19 is far in the future, but I note a robust degree of herd immunity to the inroads of rationality. (From Facebook.)

I don’t know how the whole herd immunity thing is going, and a vaccine against covid-19 is far in the future, but I note a robust degree of herd immunity to the inroads of rationality. (From Facebook.)

I’ve been thinking about the response to the anti-quarantine protestors. I thought at first that it would be good if their actions had some consequences — that it would be fitting if they died of the disease, that there would be a “Darwinian” logic to that outcome. But then I remembered a verse from last year’s High Holidays. “Do you think God exults in the death of the wicked, and would not prefer that the wicked turn from their evil way and live?” (Ezekiel 18:23). What gets to me, and probably more than just me, is that we cannot convince the protestors, and Trump followers in general, that we are right. Maybe a great orator, a great trial lawyer, a great preacher could do it, but not me, not most of us. And we have to watch as they recklessly harm themselves and harm everyone whose space, within 5’11”, they invade. This great impotence, stemming from our compassion, is what angers us most of all. If we can do nothing, we turn to God, and what are His priorities? To let them live in the hope they will figure things out, a higher priority than immediate, visible punishment. We are left with that vexing reality. We can protect everyone we can, but it is not God’s priority to make a moral lesson out of those who ignore us.

April 17: The city of Chicago and the campus have been closed down for about a month. The library, most businesses and restaurants, and the building where I have my office are inaccessible. The parks are off limits. Summer travel is canceled. I stay at home. It’s not the end of the world, but it is an interruption of many of the things in the world that I rely on to make my life interesting, pleasant and meaningful: I mean meeting my classes, holding office hours, going to talks and conferences, traveling, having coffee with people, cooking for friends. It will be months before I can do any of those things again. With all those things suspended, and the word “social” now locked into partnership with its near-antonym “distancing” (not to mention the symptoms of unstopping decline into Caligula-like government by caprice), this house is my refuge.

I am grateful to have a house in which to be confined for the duration with four people particularly dear to me. But all five of us have, or should have, lives and connections outside the narrow family circle: we thrive on the friendships, rivalries, news, contacts, that each brings back at the end of the day like ants returning to the nest. Email and videoconferencing don’t substitute for this shuttling away and back—not least because whatever pseudo-sociality we can now enjoy with the outside world is done in the presence of the whole family.

It would be worse without the telephone and the internet, but now, like those who lived through disasters of the past, we are finding out what we are made of. We are thrown back on our own resources. Our resources fortunately include, along with sacks of rice, cans of beans, and boxes of ramen, a few thousand books, to say nothing of other paper goods, and if the electricity fails and the Internet goes off, I can always light a candle and read Boethius, Montaigne, Li Qingzhao and Ring Lardner.

The moment I have said this, someone will complain that I’m speaking from a position of privilege. But books are cheap: most of mine were picked up used for a few dollars. The skill to choose them and the desire to read them weren’t acquired all in one place: some of that came to me for free, as a family heirloom, and some of it was handed on by teachers salaried on my behalf by non-profit institutions, public and private. I’m grateful for those lessons, for the shaping of the reading self that I underwent in those pre-social-isolation days. They were preparing me for this.

But let’s suppose the basement floods or the house burns, and the reader is left with nothing to read. If anyone asks what the humanities are good for, here’s my answer: the humanities are the arts that teach you how to have a meeting with yourself when even Zoom stops working.

Suspension: the Stoics, echoed by the phenomenologists, called it “epokhē.” It’s what happens when the object of your intention is taken away and you’re left with the pure structure of intending. Life feels more like that every day.

and woe befall whoever questions it.

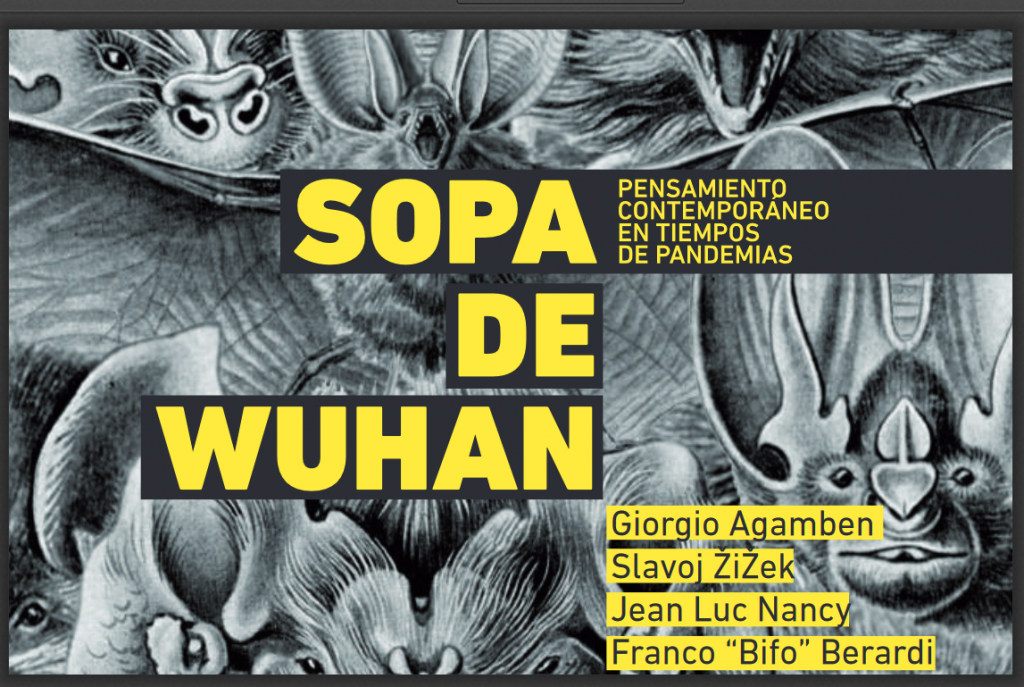

I just learned about this compilation, haven’t had time to read it, but it easily wins the prize for most unfortunate title and cover design of the year. (Called to my attention by Flair Donglai Shi.)

A friend sent me this. Messaien wouldn’t have liked it, but I did, and so have all members of my test kitchen of 4.

I understand from the media that the coronavirus lockdown has been a heyday for porn sites, so much so that they’re opening access to all and sundry. Well, hooray for them and hooray for their users. I might as well admit to my perversion and see if there’s a site that caters to it.

I like watching sweaty girls go up against 100 or so men and women armed with devices of wood, string and brass. I like it when they gasp. I like it when they strain. Their expressions of satisfaction when something goes right transport me. They don’t have to be wearing particularly revealing clothing, but they usually are dressed in something a bit showy, not that you see much of that when they’re in action. As for the action, well, they are attacking a toothy, long-tailed, black monster with their slender arms and fingers. I cheer for them and expect them to triumph.

And they do! Those girls, dear reader, or women to be more accurate, are female ninja scholars trained in the toughest dojos of Asia, Europe, and America. They go up against the Grieg Concerto, the many Beethovens, the Schumanns, the Brahmses and other Rachmaninoffs, they grind their teeth, sweat, nearly collapse, and at the end someone brings them flowers.

I used to see this spectacle two or three times a year from the fourteenth or twentieth row, having paid handsomely for the privilege. Now Youtube gives my scopophilia nearly endless license, if I’m willing to be interrupted every ten minutes by an ad for some grammar correction app that I, having learned Latin by the sweat of my brow, don’t need. Comely maidens in the spring time of their lives bang out piano concertos, encores, and encores of encores. The camera follows their every move. Mais O, ces doigts d’enfants, tapant au Gewandhaus!

However, there are figures and examples (yes, we fallen subjects need figures and examples) to show us what engagement with music, yes, music, not soft porn, by an uncompromising and straight-faced yet admirable executant would be. The red dresses, high heels and sequins of the others fall away. Let Hélène Grimaud receive my imaginary bouquets, not that she requires them in any sense. She’s photographed, not by chance I assume, in a non-voyeuristic way that shuffles all that heaving-bodice stuff out of sight. When I wake up at four in the morning with music ringing in my ears, it is with a thought of her nimble action, end-to-end memorization of the score, and oh-so-rare smile.

Our kids’ school started remote learning today. It’s mediated by a platform called Seesaw which, despite having early notice of the likely surge in demand, hadn’t prepared the necessary servers and so crashed repeatedly (does this remind you of anything else?). We thus had three computers running different grades’ version of Seesaw remote learning, all timing out and crashing at once. The kids were already unhappy at the unexpected transformation of their parents into teachers. We know they can behave themselves at school, but they shed all those manners and pretenses of citizenship at the door, and now they had angry and impatient teachers who were beside them tapping at virtual buttons that were frozen, watching the precious fruits of twenty minutes’ coaxing suddenly vanish without a trace, and losing the point of the lesson (as well as any pedagogical authority). It was, in short, a rout, a fiasco, a débâcle, a hot mess, made worse by the thought in this parent’s mind that the graduate seminar due to be taught in a few days on an analogous platform will probably turn into a similar plate of slimy entrails.

It gave me a headache that is still going strong as of 8:13 pm.

There’s a form of learning that humans have engaged in for millennia: a bunch of learners, willing or unwilling, gather under a tree or in a room with a Subject Supposed to Know, who tells them stuff and maybe elicits questions better than the pre-planned palaver. Since remote learning is a skeuomorphic derivative of that, it is most effective when the game is played among people who have already developed the skills and instincts that go with sitting in a room with a bunch of other learners, giving side-eye to the loudmouths, locking eyes with the smartest or most attractive fellow seminarians, thinking (or not) before speaking one’s piece– it is therefore a foreign idiom to kids who are still learning to sit still and take turns. All the more when those kids are used to screens tempting and cajoling them with ready entertainment all the time: now, in an abrupt betrayal, it’s a dead video of their kindergarten teacher sitting on a sofa and trying to be cheery. To hell with that, they think, and behave accordingly. The parent, who has a million and two other things to do but is pushing them out of mind for the duration of the lesson time, gets stricter and stricter as discipline fails, and before long even a friendly inquiry (“is that how your teacher tells you to write an N?”) makes Child Two cut loose with a screaming tantrum and existential denunciations of all possible being and beings. I’d rather be on the golf course, and I hate golf.

Tomorrow, episode 2, and I wish I had a stash of happy pills.

Our correspondent in Pagliara (district of Messina), where the virus has not made itself known but the lockdown is strict as everywhere else in Italy, writes with a few reflections about the state of emergency.

If I think about the world in movement, excluding all physical definitions of “movement,” the one definition that comes to my mind is: production. A world in motion is a world that produces, whatever it may be that gets produced. From childhood on we are trained to produce, encouraged to do so and rewarded when we’ve made something, even a poop. Praise, candy, toys, pocket money—how many rewards do we receive from life? Action and reward. This pairing creates on one hand a condition of permanent immobility (society is stuck in childhood), on the other a persistent enslavement. At this point, to say that the world has stopped because of coronavirus seems to me no more than the recognition of a long-established fact: we haven’t stopped, we stopped a long time ago. The illusion of movement is given us as a “gift” by those in a position to manipulate the levers of government and production, those who are so good at manipulating them that we too carry them out in relation to ourselves and others, in the belief that no other worthy form of life is possible. To stop is frightening, because a world that stops its supply chains is, paradoxically, a world that breaks its chains and opens its cages, that reveals empty spaces that we no longer know how to fill, because we are trained to fill the gaps and we aren’t able to live in them, we have no idea how to do that. In saying this I do not intend in any way to express gratitude for circumstances that, like the current virus, attack life; I merely want to use this event as a pretext for shedding some light, for understanding the immensity of our error in binding our existences to the market, to business, to finance, and in making our lives depend on choices that are imposed on us together with the illusion that it is we who make those choices.

The adventurous history of the School of Chartres comes to mind, though I don’t know what prompted it: a School that tried to reread Aristotle in light of Christian thought. What sorts of ideas would have been active in the world if that School had not been censured? The same could be said of our system: was there no alternative? At that point there was some movement, but today our system no longer generates movement, and so, exactly as a virus does, it agitates below the surface to block movement, to forbid any human reaching toward abstraction, freedom, toward a form of growth concerning not only the economy but rather our consciousness of the self and of restraint. We have lost our own center, it has been hidden from us, our distraction from it has lost us our relation to the world. The illness begins here. After that come viruses, influenzas, downfalls.

(Original text follows.)

Se penso al mondo in movimento, escludendo tutte le definizioni fisiche di qualsiasi “movimento”, l’unica definizione che mi viene in mente è: produzione. Un mondo che si muove è un mondo che produce, non importa che cosa. Fin da piccoli siamo educati a produrre qualcosa, incoraggiati a farlo e gratificati quando facciamo qualcosa, anche la cacca. La lode, la caramella, il giocattolo, lo stipendio, etc., quanti premi riceviamo nella vita? Azione e premio. Binomio che ha generato da un lato una immobilità permanente della nostra condizione (la società è ferma all’infanzia), dall’altro una perenne schiavitù. A questo punto, dire che il mondo, a causa del coronavirus, si è fermato, mi sembra soltanto la constatazione di un dato di fatto già in essere: non ci siamo fermati, siamo già fermi e da tanto tempo. L’illusione del movimento ci viene “regalata” da chi sa dosare gli strumenti del governo e della produzione, da chi sa dosarli così bene che anche noi li mettiamo in atto nei confronti di noi stessi o di altri, pensando che sia l’unico modo possibile per una vita dignitosa. Fermarsi però fa paura, perché un mondo che ferma la sua catena di produzione è, paradossalmente, un mondo che spezza le catene, che apre le gabbie, che mostra spazi vuoti che non sappiamo più come riempire, perché siamo educati a riempire i vuoti, non riusciamo a vivere in essi, non lo sappiamo più fare. Queste mie parole non vogliono certamente esprimere gratitudine verso gli incidenti che, come l’attuale virus, intaccano la vita, ma prendono spunto dall’incidente per cercare di fare luce, di comprendere quanto sia grande l’errore di legare la nostra esistenza al mercato, agli affari, alla finanza, di farla dipendere da scelte imposte con l’illusione di essere noi a farle quelle scelte.

Mi viene in mente, non so richiamata da cosa, l’avventurosa storia della Scuola di Chartres, dove si cercava di rileggere Aristotele alla luce di un pensiero cristiano. Quali idee avrebbero agito sul mondo se quella Scuola non fosse stata censurata? Lo stesso si potrebbe dire del nostro sistema: non c’era un’alternativa? Lì c’era del movimento, invece adesso il nostro sistema non genera movimento, anzi, proprio come un virus, agisce in profondità per impedirlo, per fermare ogni tensione umana verso l’astrazione, la libertà, verso una crescita che non può riguardare soltanto l’economia, ma riguarda esclusivamente la consapevolezza del sé e del limite. Abbiamo perduto il centro di noi stessi, ci è stato nascosto, ne siamo distratti e con esso abbiamo perduto la relazione col mondo. La malattia nasce da qui. Poi ci sono i virus, le influenze, le cadute.

I am not a hoarder of anything but books and CDs, and I have enough for the current purpose. It’s therefore been a shock to go to a cleaned-out Costco and see the work of real hoarders — whole sections cleaned out of paper goods, bottled water, alcohol, and other disinfectants, and baklava. I must confess that I took the last box of baklava but only after seeing an entire pallet of baklava higher up on the shelves. I do wonder how Minnesotans are doing; they are loath to take the last piece of pie, the last spoonful of Tater Tots, or the last Ole and Lena jokebook. They would probably wait for a sad person to come along, buy him the last Ole and Lena book, and walk out of the store.

The other sad thing about Costco unter militärischer Verwaltung is the amount of shouting and ordering that goes on. I suppose it’s needed to herd people and curb them from hoarding, but it feels to me like being in a detention center, admittedly a gentle one. I am obedient, I smile, I make little jokes, but there is a space between the TV aisles from which no one returns, and I note the endless line of people headed there. Perhaps they climb inside the giant screens and are suddenly in a better world.

Only one person spoke to me, about the circuitous lines to the checkout: “Why do they make it like Disneyland?” “Because there’s going to be a ride at the end.” I did not tell her that The Happiest Place On Earth had been shut down earlier that day.

It took me a while to shed the feeling of ruin: the titan of American consumer capitalism slain by its own shoppers. Its guardians will preside over less and less until finally, they are guarding perhaps one bottle of commodity Rosé and a box of Godiva Hollow Chocolates — perfect for that one post-apocalyptic romantic interlude between two chairs in a decorator-grey apartment. Then they will be at the end of their labors. They will run the End of Day Report, reconcile the tills, shut the lights, and pack up. “As it was for our fathers, so let it be with us,” they pray, and perhaps from there, outside of the big concrete box, their words will take flight.

I was dismayed to see the quasi-automatic reply to the coronavirus situation registered by Giorgio Agamben, author of Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. For him, coronavirus has replaced terrorism as the Big Threat that legitimates totalitarian control– the new excuse for prolonging the “state of exception.” In his defense, I’d point out that it was posted on February 25, when there were only 219 cases reported in Italy and 11 deaths. But simple math would have permitted the distinguished philosopher to predict scenarios of transmission rate (in a range from worst-case to best-case) and consider whether measures to slow the spread were warranted. I think the reflex of likening every act of state power to the death camps of the Second World War has the disadvantage of blocking the question, where are the death camps we want to avoid? Are they visible in the empty streets of Rome and Palermo, or are they visible in the overcrowded ICUs of Bergamo and Milan where, lacking an adequate number of respirators, doctors have to decide which patients get a second chance at life?

It’s even more dismaying to see that, at that same moment, the kind of people whom Carl Schmitt would be cheering on to seize power and destroy the opposition in the name of the Ausnahmezustand were saying exactly the same thing as Agamben about pandemic hysteria advancing state encroachment. I put it down to coincidence rather than conspiracy. Schmitt happens. But good people find ways to keep Schmitt from happening. Flatten the curve, friends, even if the curve was a back-of-the-envelope schematic.

Geneviève Azam

(Le Monde, March 13, 2020)

The world seems to be in a state of instability. Warnings pile up: unbearable inequalities, dependence on uncontrolled technical systems, the accelerating rate of climate chaos and of the extinction of living things, the uprooting of millions of people with no land to welcome them, pollution, a financial system on the verge of exploding, and now an epidemic: a long list of threats that undermine one’s confidence in the future, even the immediate future. We are not experiencing some momentary crisis, to be dealt with by means of a few corrective measures that will bring us back to “normal.” We face irreversible changes and outsize accelerations, exemplified in particular by ecological catastrophes. We are living in a time of collapse.

It is a political collapse as well. For decades now, states have sacrificed the public sphere, the commons, and have turned their societies into “appendices” of the market and the economy, following the expression of Karl Polanyi in his The Great Transformation (1944)—an economist who saw the vast “self-regulating” market as a “Satanic mill” and one of the causes of the fascisms of the 1930s. Since the coming of neoliberalism, the mill has expanded and overheated. As a result of adapting steadily to the laws of competition, life, in all its forms, human and non-human, is threatened—not just on a geological scale but on a historical one. History, which modernity conceived as the product of sovereign human action, no longer wholly answers to us. The earth and life forms strike back. We have triggered uncontrollable events that trigger one another. The neoliberal narrative of growing quality of life and health collapses as well.

Global capitalism responds to these events by a biopolitics like that already announced by Michel Foucault: the adaptation of populations takes the form of data collection, tracking, selection, confinement, walls, refugee camps, surveillance and repression. With the addition of artificial “intelligence” and algorithms, it is now carried out in more “rational” and industrial fashion.

But human creativity will not be controlled. Imagining collapse is also a shock that, far from paralyzing thought and action, seems on the contrary to liberate them from the progress-minded expectation of a future that sweeps us away from our presence in the world. It reveals the stakes and causes us to take leave of our illusions of a gradual transition, of an “end to the crisis” in linear and reversible time. It awakens the coming generations, whose concrete presence and whose commitments restore the meaning of world-making and shield us from apocalyptic fantasies that depend on the loss of meaning. To live in the world, to live on the earth, to reclaim lost territory, emptied, destroyed or defaced territory, is the common ground of many kinds of experience—concrete experiences of conviviality born from earthbound communities that include humans and non-humans and confront predatory, deterritorialized oligarchies.

It is by refusing the techniques of catastrophe management, otherwise known as “reforms,” that a broken society can re-form itself, that other ways of life can take shape. The roundabout communities where “yellow vests” gather, those non-places of a life condemned to circulation without attachment, emerge from disaster. Conviviality rediscovered amid living things: it can come through ageoecology, agroforestry, permaculture, shortened production and consumption chains, workplace cooperation, social solidarity, simplicity and sharing, a welcome to migrants, occupation of territory, convivial, low-tech technologies. Society re-forms itself by abandoning the institutions of consumerism and the Uber-ized life, in such experiences of “pure, unalloyed joy” as were described by Simone Weil, observing the steelworkers’ strike of 1936. In place of the acceleration that shears off all attachments, rediscovered time takes its pace from living matter despoiled by the cadences of the industrial world. Conviviality becomes meaningful when lawyers on strike come together to secure law and justice, when teachers refuse to participate in algorithmic pedagogy, when railroad workers contest the dehumanization of closing ticket-windows, when over a thousand researchers call for disobedience, when the scale of local government becomes a political sticking-point of resistance to expanding urbanization. In a world this brutal, conviviality has to be fought for.

Geneviève Azam (economist, essayist, member of the advisory board of ATTAC, www.attac.org) is also the author of Le Second Manifeste convivialiste, Actes Sud, 144 pages, 9.80 euros.

(Unauthorized, volunteer translation from the French by Haun Saussy. I welcome comments from the author, even grumpy ones.)

Parents of small children have written en masse to protest my latest song suggestion, so here’s something a little more uplifting. May it buoy you through the present crisis and obligation to perform “social distancing.”

P.S. Here’s a clip of R. Stevie not staying home:

In case you’re bored in quarantine or forced idleness, here’s something to do.

Like you (probably), I get about 60 emails every day from one or another political campaign begging me to send money. I hated the Citizens United decision the day it was announced, and I am reminded 60 times a day of why I hated it: the lifting of limits on campaign spending means that every candidate, even the ones who are against the disproportionate influence of money in politics, must constantly be on the treadmill of asking, asking, asking.

The campaign strategists know that the typical donor is receiving, oh, 60 emails a day asking for the same thing. So they need to get our attention. One method has been to go all Affect Theory and Drama Queen/King on us, staging freakouts in the subject line of the aforementioned emails.

I’m not unresponsive to affect, but the fakery and the emotional overdoing get on my nerves massively. I haven’t called anyone’s campaign hotline to say “You might have had my $5 because of the policies you push, but you alienated me with those ‘All is lost’ ‘Give up hope forever’ ‘Desperately asking for $2’ messages.”

One campaign, by a young fellow challenging a Republican stronghold out west, has been particularly egregious in playing the emotional card. The picture that comes with the email, of a well-put-together guy with a nicely-groomed beard, jars with the shrieking paranoia of the messages. A sequence:

confused

accepting defeat

DESPERATE –> Trump coming tomorrow

I can’t sleep

please help

emergency (please read – don’t delete)

shutting down our office

devastating

shutting down our office

Our hearts are EXPLODING!!

hey are you okay [NAME]?

CATASTROPHE — packing our bags — in complete shock

[CANDIDATE] is freaking out

Republicans HUMILIATED (incredible, [NAME]!)

[NAME], let me explain

The cumulative effect is a kind of emotional abuse. And delete as you will, block as you will, the campaigns always find a way into your Inbox with another sender name. Give me a candidate who’s level-headed and talks about the issues, not emotional states. There’s enough turbulent affect out there already. Talk to me grown-up to grown-up.

I don’t have a television. But I guess it’s reasonable for people who have one to treat presidential candidates as potential roommates and rank them on the relevant criteria: fun to be with? colorful personality? somebody you won’t argue with a lot? grouches about the same things you do? presentable to the neighbors? has his/her own car? For if you have a TV, this person is going to be your roommate for the next four years, yawping and squawking at all kinds of moments while you’re cooking, looking for your glasses, or wishing you were somewhere else.

Being televisually impaired forces me to put aside the likability and electability measures and make lists of policies. The presidential election is actually a job interview. What are the criteria? Can the person do the job (does the person even know what the job is)? What about disease, unemployment, debt, inequality? If X happened, what would you see as the top priority? The second priority?

Now that my top candidate has bowed out, those who cheered her on with me are talking as if there’s no hope, as if the remaining candidates are each a take-it-or-leave-it package of inferior executables. But we know that policy statements are just words on paper unless there are the majorities to enact them, and policy ideas don’t go away when a candidate folds up the campaign. We can actually (radical notion) separate the candidates from the policies and insist that the policies of candidate P become a goal for candidate Q as candidate Q goes from the primaries to the general election, because we won’t stand to have them folded up and recycled along with the lawn signs for candidate P. The primaries should be testing grounds for ideas, recruitment fairs for high-level appointments, and thus a forum where policies get traction, not a demolition derby where a cartoon character annihilates another cartoon character and all he or she stood for.

We have over-personalized the presidency, loaded it with too many launch buttons, and it’s time we started pulling back on the cult of personality. How about the cult of policy? Let a hundred wonks wonk, I say. Those who can’t wonk the wonk have no business talking the talk.

When I have to stop the many-colored pinwheel of daily tasks and ask who my four or five Real Enemies are, one that has always made the shortlist is American Exceptionalism. That is, the belief that we as a nation are special; not subject to the laws of nature or social development that drag down other, lesser nations; guaranteed a place in the sun by God Himself and destined to get our way, even if we have to throw tantrums and bomb cities to do it; and no matter what we get ourselves mixed up in, irrefutably, permanently, righteous. Though I would love to claim such bragging privileges for myself and my 400 million friends, I know it’s not fair, and fairness ought to come out on top.

A winter morning spent riffling through the DSM-5 will give us some new language wherewith to seize and band this rapacious volatile. “A pervasive pattern of grandiosity (in fantasy or behavior), a constant need for admiration, and a lack of empathy.”

Yep, that’s us.

It goes on. The pattern is usually “established by early adulthood” (when would that be, in our 250-year history of legal existence? The War of 1812? The Jackson Administration? The Trail of Tears? The Missouri Compromise?):

… and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by the presence of at least 5 of the following 9 criteria:

A grandiose sense of self-importance;

A preoccupation with fantasies of unlimited success, power, brilliance, beauty, or ideal love;

A belief that he or she is special and unique and can only be understood by, or should associate with, other special or high-status people or institutions;

A need for excessive admiration;

A sense of entitlement;

Interpersonally exploitive behavior;

A lack of empathy;

Envy of others or a belief that others are envious of him or her;

A demonstration of arrogant and haughty behaviors or attitudes….

I think we can check all 9 of the 9. Saying “the other nations do it too” isn’t a valid excuse: we’re talking about your maladaptation, chump, and you are, if the truth be told, a largish specimen of the kind.

With these personality distortions on our rap sheet, perhaps it was inevitable that we would sooner or later choose the most monstrous exhibit of these traits to be our face to the world. Be that as it may, now our national narcissism faces a problem that can be solved only by science, care, and cooperation– disciplines that the narcissist finds intolerable. For science is humbling (the virus doesn’t give a damn who you are), care requires sacrificing some of your infinite Me Time to look after others, and cooperation may involve accepting somebody else’s leadership (see above under: science).

National narcissism responds by “splitting” (I’ve gone back to riffling through the DSM, mixing the entries for narcissism and for borderline personality disorder), in an effort to divide the Me (entirely good, powerful, healthy, and blameless) from the Them (dirty, infected, flawed, repulsive). Let the walls rise! Cut off all communication, push the huddled masses back onto the boats! Feed the racist rabble-rousing! For the sake of nurturing disgust, fantasize about Chinese gulping down bat soup and similar unspeakables! Downplay the seriousness of the disease, because it can’t possibly affect a person like you and you don’t have empathy for the lesser breeds anyway. Deny it flat-out, because your words make reality, and the virus will fade into nothingness at your say-so. Get out that Sharpie and tell the winds which way to blow!

None of this is going to help. We are all in the path of the damn thing, and what will get us through is frequent hand-washing and accurate data collection and transmission. And a dose of blind luck.

My sympathies go to the people of Wuhan. Their troubles have been augmented by another national personality disorder, but I don’t feel like finger-pointing just now.

Hey there fans and inveterate enviers! I’m sitting on the top of the influencer world now, occupying my school-of-Stickley rocking armchair (bought second-hand in 2011 in St. Joseph, Michigan, $200) while electricity spills from flame-shaped bulbs (Ace Hardware, $6.99 for 6) after being generated from good old Sol (free; prices for photovoltaic setup and installation vary by locality). And in front of me is a copy of Walter Goffart’s Barbarians and Romans (Princeton University Press, 1980; paperback; $9 used from Powell’s Bookstore, 57th Street, yesterday afternoon). When I’m done with this I have a couple of reviews to check over for a journal and a backlog of student papers. Approximately four reviews and two papers from now, I will want lunch, and though it’s early yet I suspect this may involve some frozen green scallion pancakes from the Chinese market. I’m benefiting from free delivery of the bass track of some rap song, courtesy of my neighbors who are warming up their car. Life is good, especially when I consider all the less exciting things I could be doing.

There should be a word for the following situation, common in my crowd. I knew Walter Goffart for years as a pleasant person to have tea with at the Elizabethan Club in New Haven. We knew many of the same people (often medievalists, now that I think back to it: the Viking historian, the Old English philologist, the person reconstructing Anglo-Saxon pedagogy) but didn’t often talk shop, preferring to direct our mild jabs of irony at the Times from that morning, the latest idiocies of politics, and new novels that one or two of us had read and the others were putting on their to-read lists. But it turns out that this person I knew casually has written an astonishing book. The phenomenon I am referring to might be called the “The Crazy-Haired Dude Who Gave You a Quarter For Mowing His Lawn Was Albert Einstein” double-take.

It was just one of those things that I’d always known that Rome fell (476 AD, right?) to barbarian invasions. My ten-year-old was asking me about it the other day, which is part of why I was standing in front of the medieval section at Powell’s. I could draw you a picture of those barbarian invasions. Hirsute, armed to the teeth, mailed, fist-shaking, horsed, the rude strangers came pouring over the horizon and broke through the walls of one Roman city after another while senators and matrons ran screaming down the forum, tangling their feet in their long curtain-like clothing. But Walter asked what the records showed, and the story is different: groups of foreigners showed up, a few thousand per group, on the fringes of the Roman Empire, and asked to be taken in. They sometimes got allocations of land, sometimes received regular payments from the public purse. In short, it was the usual way that a powerful state, even a somewhat depressed one, handles an influx of refugees, and in time the refugees became a settled population of taxpayers. Goffart offers a story of “undramatic adjustments between Romans and barbarians” (p. 4). It is finely documented on the basis of local sources from across the empire, and makes one wonder whether the dramatic story of invasions and migrations might not be, as they so often are, a construction designed to prepare our minds for the inevitability of policies that seek to “close the floodgates” against the “barbarian tide” menacing Europe, or England, or Bognor Regis, as the case may be. “The attractive power of the empire, typified by the government’s welcome to foreign military elites, had a more certain role than any impulse from the barbarian side in establishing exotic dominations on provincial soil. When set in a fourth-century perspective, what we call the Fall of the Western Roman Empire was an imaginative experiment that got a little out of hand” (pp. 34-35).

It’s always a part of the “Einstein and the Quarter” scenario that when the penny drops, you wish you were back in that clubhouse drinking tea with the man who wrote the provocative book, so you could ask more specific questions — thereby defying, if need be, the tacit rule against talking shop. I’m sure I will be mentally translating the Goffart doctrine into terms suited to Chinese uptake in the coming weeks.

(Like this lifestyle influence column? Guess what — there’s no link you can click on here that will scrape your data and accept your money! Just scrounge around your own neighborhood for used furniture and used books — on paper, please — that will make living through the next disaster or epidemic tolerable.)

New York Times: Mirella Freni, Matchless Italian Prima Donna, Dies at 84

Opera fans have a tendency to live in the past. “Yes, I’ve heard so-and-so, but if you listen to someone else’s 1951 mono recording of ‘Voi che sapete,’ you will see that this new singer is just an epigone.” If one has time and a record library, the years seem to drop out. I can hear Ring cycles by half-a-dozen conductors across the whole of the twentieth century, and when I am enchanted, I forget that three of those conductors were Nazis; there are just voices in time. But time does advance, leaving a trail of dead singers who now represent marketing opportunities for the record labels. I expect bookcase-breaking sets of Ms. Freni’s back catalog by fall; I will likely buy one. I admire her integrity, her skill, and her art; people seldom get to be so good at what they do.

After a few days in Arizona (beautiful sunlight, sharply-outlined mountains, constant reminiscences of Wile E. Coyote), I recall how many times the newspaper and conversations overheard around me attested to a general meanness. People talked about an “invasion” on the southern border as a matter of course. As if folks like them had not once been invaders! And grumbled about Californians “invading” as well, with their strange clothing and mores. The newspaper brought news of the state legislature attempting to get legal cover for punishing cities or districts that passed any local ordinances that ran counter to state policies. Or rather, not “any,” but specific ordinances seeking to protect migrants, undocumented people, minimum-wage-earners, and otherwise vulnerable humans. The state seeks to mandate meanness. A kind of absurd climax was provided by a proposed act that would disqualify most kinds of “emotional support animal” on public transport. “Owning the libs” at its finest. I would advocate separating people from their emotional support firearms in every context but the national defense, how about that? It wouldn’t even be mean.